The Radiologist

We can't build great teachers if we can't spot great teaching. Unless we train leaders to see beneath the surface, feedback will remain blind.

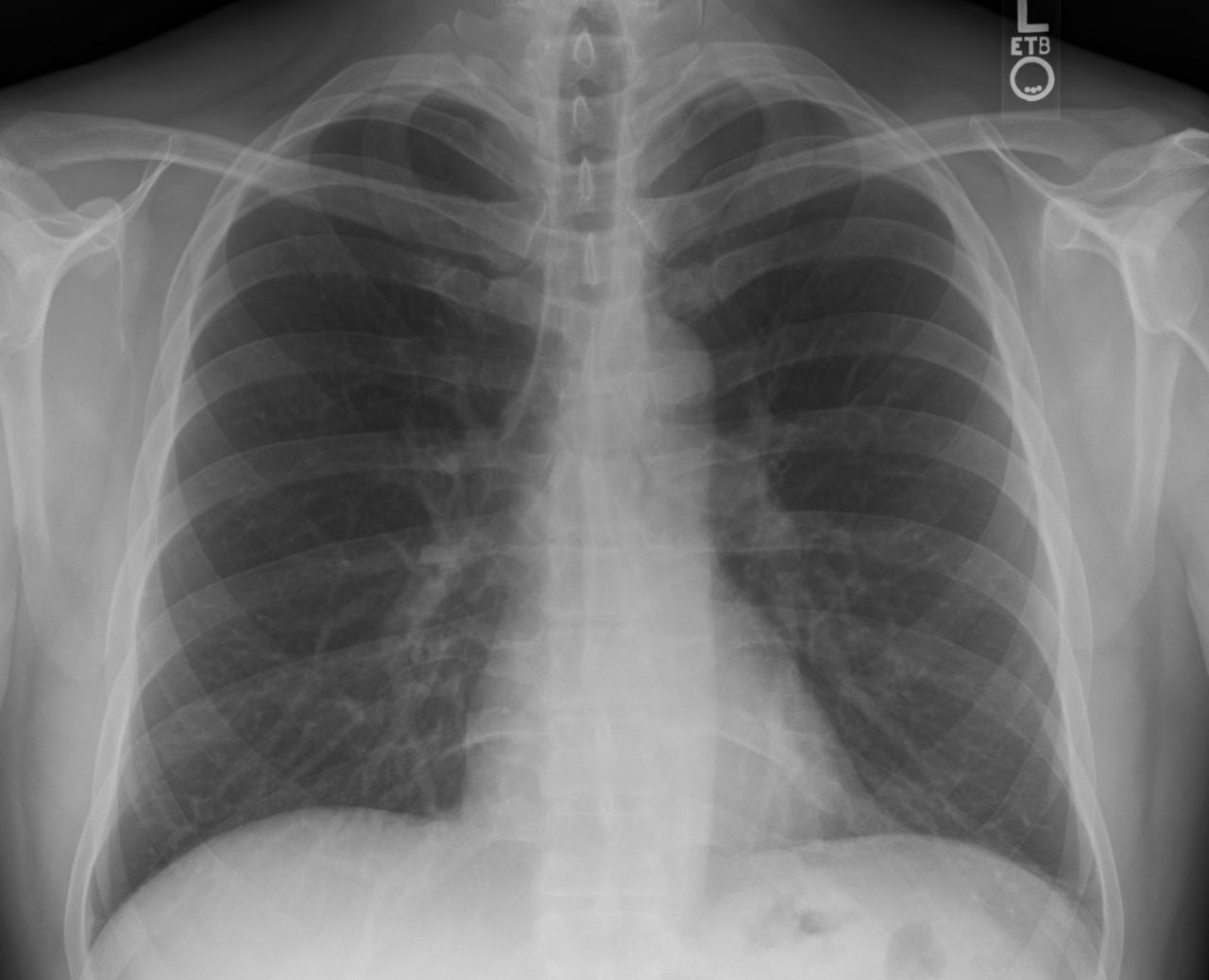

The above image isn’t too hard to decipher. Most people would recognise it as an X-ray of someone’s chest, showing ribs, some vertebrae and what look like shoulders. With a bit more knowledge, you might also spot the clavicle, sternum and outline of the heart, as well as notice that nothing looks broken or fractured. A professional radiologist would, of course, see far more: they might be able to comment on the person’s age, size, or signs of infection or cancer. They would see things that a layperson would not.

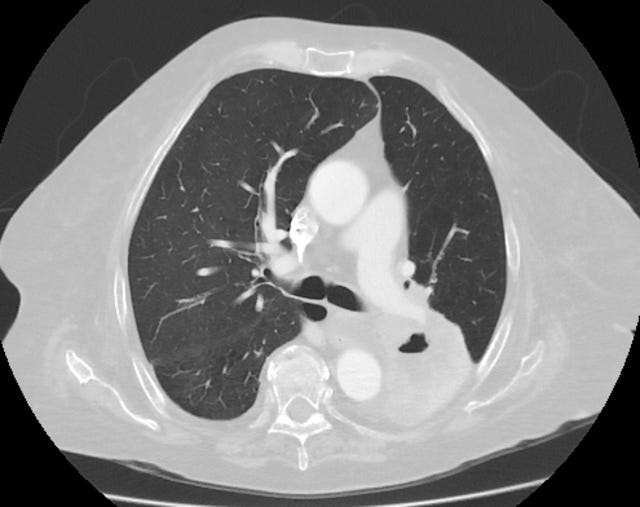

Let’s try another image:

This one’s a bit harder, and most people at a glance won’t be able to tell what it is. Unsurprisingly, a radiologist could - they’d recognise it is a cross section of the lungs. They would tell you to imagine that the patient is lying on their back: you slice through their chest and look at the cross-section you’ve made. You’d see the backbone at the bottom, two large grey masses for the lungs and some ribs surrounding them. In this case, with the right knowledge, you’d also spot signs of disease: this image (apparently) shows “Cavitation of a lung squamous carcinoma, infrahilar, affecting the left lower lobe.”

The image is from a CT scan, which is a technique used to take pictures at 5 mm slices through the human body. They are hard to interpret because the angle is unfamiliar, and the bodily structures often look blobby and messy. A radiologist, of course, would have no trouble interpreting it and could give you chapter and verse about the patient and their health.

I imagine nothing I’ve said so far is particularly controversial. “People who are trained to interpret CT scans are better at interpreting CT scans than people who aren’t” isn’t exactly a hot take. What might be more controversial though is the following statement:

Most middle and senior leaders in schools observe many lessons, but, like a layperson viewing a CT scan, do not know what they are looking for.

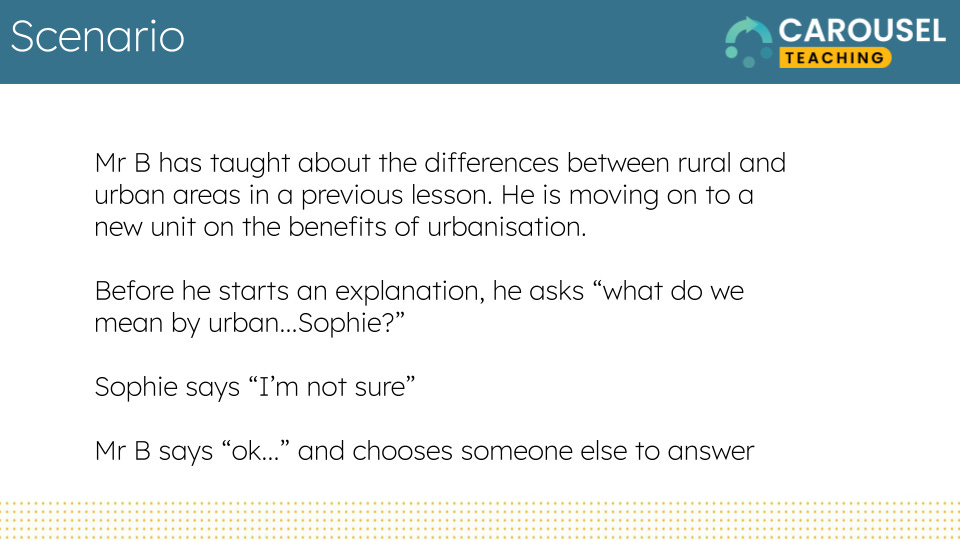

Let’s take a simple classroom example:

This looks like a pretty straightforward and common classroom scenario that lasts less than 30 seconds. Teaching isn’t straightforward though, and as observers there is a lot that we could think about in this tiny snippet:

Mr B puts the name at the end of the question: This is good, as lots of teachers don’t do this. It’s a critical step in achieving high attention and participation classrooms.

There is Wait Time: This is good, and often teachers don’t do this, or don’t leave enough. In this case, is there enough Wait Time? How will I as an observer know if it was enough?

Wait Time is called before the name: This is also good. If the Wait Time comes after the student’s name has been called, other students will switch off and attention levels will fall.

Mr B is doing a prerequisite knowledge check: This is good, lots of teachers don’t do this. It allows him to ascertain whether or not students are ready for new content.

When Mr B goes over old content, he does it via asking questions rather than merely reminding students: This is good because it gives the students an opportunity to do retrieval practice.

How long ago was the last lesson? This will affect the challenge of the question due to the propensity of memory to fade.

Did Sophie have her hand up? Would it matter if she did?

Is Sophie an Indicator student?

Does Mr B have rules in his head for deciding who answers which question (targeting)?

Where is Mr B standing: is he in the corner of the room, or is he in the center?

Is Sophie speaking loudly enough for everyone to hear?

When Mr B talks to Sophie, is he keeping his head up and eyes scanning the room, or is he locked into eye contact with her, thereby losing track of other students and potentially communicating that this is a one-to-one conversation?

Why didn’t Mr B use mini-whiteboards? Using boards would have massively increased the assessment information he received.

How does Mr B know that Sophie really doesn’t know, maybe with a bit of prompting she could have answered?

When Sophie says “I’m not sure,” why does Mr B assume she really doesn’t know? Maybe she just wasn’t listening and didn’t even hear the question.

How is Mr B going to ensure that going forwards Sophie does know? Is he going to Loop back to her? If so, why hasn’t he told her that he will do so?

Observing lessons, like interpreting CT scans and X-rays, is a skill. Like other skills, it can be broken down into its components, communicated to others, and practised until it is improved. Just like a radiologist examining a scan, a good observer should be able to walk into any lesson, anywhere, at any time, and ask questions or make statements like the 16 raised above.

I don’t pretend that acquiring this skill is easy. After all, if we continue stretching our analogy, radiologists will typically train for over ten years before they are fully qualified. So it may be hard and a long road, but it’s unquestionably necessary.

I also don’t mean to cast aspersions on anyone, and my “controversial” statement above isn’t designed to make anyone feel bad. It’s not a leader’s fault if they haven’t been adequately trained to do something. Nor is it any individual person’s fault that, as a system, we haven’t yet prioritised training leaders to observe lessons. But observing others is critically important work, and giving feedback is a privilege. We have a professional and ethical duty to take it seriously, and the least we can do for our colleagues is to put in the hard yards to be ready to deliver it.

First, we need to identify and define the components of effective teaching and build a clear model of what they look like in practice. We then need to establish when these components should be visible, and what lessons look like when they are not.

If we ever need an X-ray or a CT scan, we’d only want a true radiologist to be interpreting it. If a colleague is going to observe us teaching and give us feedback, we should be able to expect the same level of expertise.

Carousel Teaching is designed to help teachers and leaders understand the core components of effective teaching. To become a teaching radiologist, check our Carousel Teaching here.

This is so powerful, Adam. Thank you!